Who needs another Muhammad Ali documentary? Creators of the new PBS documentary Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami succeeded by taking on a fresh approach – how did he become Muhammad Ali? And why is he and forever “the greatest”? We had a chance to chat with the producers, Gaspar Gonzalez and Alan Tomlinson.

Scores Report: Hello.

Gaspar Gonzalez: Yep, it’s Gaspar.

SR: Really enjoyed the documentary by the way.

GG: Thank you very much.

SR: So, is it okay if I just start the questions?

GG: Anytime you like.

SR: What is one thing that you guys learned about Ali that stood out when making the film?

GG: We had researched the film and subject matter extensively before we ever started. I think the thing that surprised us, not that we didn’t know about it, but how kind of compelling the material turned out to be with his relationship with Malcolm X – and how that relationship kind of evolved and devolved. We came across that snippet of film where he is being interviewed obviously after the assassination and he says something to the effect of “anybody who speaks out against Elijah Muhammad will die” which is a very stark thing to hear. I think that aspect of the story turned out to be more compelling than we thought initially.

SR: What inspired you to make this film? Why did you want to make it?

GG: It was sort of my idea and I was not a filmmaker so I took the idea to Alan Tomlinson, so you know without Alan it wouldn’t have been made a film – let’s get that straight. But I grew up in Miami, and I’m forty years old, so I’m just old enough, obviously Ali was long gone by the time I was a young kid, but there were still plenty of people around who remembered Ali when he used to hang around Miami. They remembered running into him in Cuban restaurants and seeing him on South Beach and running to and from the gym – and so I always remembered that from the time I was a little boy. Then I ended up in grad school and did a PhD in American Studies and became a cultural historian. So I was able to appreciate as a cultural historian the significance of that story – the significance of this young kid named Cassius Clay coming to Miami and evolving into Muhammad Ali here, and in some ways these memories I had as a child, you know of people who still remembered and talked about Ali, kind of came together with my professional training as a historian. I thought it was a story that really had never gotten the attention it deserved – so I took the idea to Alan Tomlinson and he thought is was a great idea and so we made the film.

SR: How long did it take to make this film by the way?

GG: Well, that all depends on how you count it. From the time we pitched it to WLRN, which is the Miami PBS affiliate. They gave us the go ahead probably February of 2006 and we went into pre-production — we conducted the interviews beginning of the summer of 2006 and through early of 2007 and we premiered the film locally in November of 2007. So, if you want to count it from the very, very beginning – probably a year and a half. If you want to count from the time we actually started shooting it was probably a little more than a year.

SR: I think one of the greatest aspects of this film is probably some of the interviewees that you guys had and incorporated in the film. I was just curious how did you find some of these people that knew Ali so personally? Was it a difficult process in locating them?

GG: No, not really. Obviously people like Ferdie Pecheco and Angelo Dundee they’re famous in their own right. A few others like Nelson Adams who was the neighbor, as a young boy he was Ali’s neighbor who is actually a prominent doctor in Miami now – and Sonny Armbrister who is the barber, who was wonderful in the film. People like that, while they are not famous per se, they are very well known in the black community in Miami and are very well know in terms of their association with Ali. Everybody knows that Sonny Armbrister was Muhammad’s barber for a long time and that Nelson was his neighbor and so I don’t know that we necessarily uncovered anybody who…I don’t think that was one of the hard things in making this film. You know Flip Shulke is a reknown civil rights photographer and he had actually put out a book in the 1990’s of his Ali pictures in Miami so, that was just a matter of tracking Flip down. So you know again, I don’t think this story was unknown, I think the story was under-appreciated and had been given sort of short shrift in other films and books and what have you – and so I think that’s what we did. We just went back and told the story the way it deserved to be told and we went to the people who can best tell that story.

SR: Was there anything in particular that struck you about your interviewees?

GG: Yes. They were all great story tellers. It’s very unusual to turn the camera on people and have them be as smart and funny and insightful as our subjects were. Almost without exception that is very unusual. A lot of times you can go to somebody who is very knowledgeable and is the perfect interview subject for the film you’re making and you turn the camera on them, and it’s deadly – you know they are just not very good at it – they are not very good at talking on camera and not everybody is. We were really blessed, I guess would be the right word, that all of our subjects were just terrific that way – which incidentally is I think which made it very easy for us not to have a narrator.

SR: Those interviews were really great.

GG: Yeah. The entire film is narrated by our subjects.

SR: What was your favorite moment while making this film?

GG: There were lots. We had such a great time in making it. Making the film was a great excuse to talk to some really interesting people. One of my favorite moments is that when we actually interviewed Angelo Dundee, who is a great guy and a legendary boxing trainer, we thought on our way out the door, we thought of this idea, we said we should take this little T.V. set with a tape player, and play the tape of the Clay/Liston fight for Angelo. You know because we are gonna be asking about the fight. And so, we interviewed him at the gym, and we set up this little thirteen inch television set with a tape deck and we popped in the VHS tape, super low tech, and we set him up on a stool and he watched the fight. Then we had him comment on the fight as it played in front of him – and it was wonderful because he actually said he did not watch that fight all the way through since maybe the night of the actual fight. He’d seen little clips of it.

(Alan Tomlinson joins the call.)

Alan Tomlinson: I’m on board now. This is Alan Tomlinson. I was waiting for the opportunity to let you know I was here.

GG: I was just telling the story of when we took the T.V. over to Angie.

AT: Yes, absolutely.

GG: And it was a great moment. He immediately fell almost into this trance and he started referring Ali as “my kid.” As “My fighter my kid” and it was like he was right back in that moment – and that made it into a terrific interview. So that was one of the things that really stands out for me and I assume that for Alan as well, but I don’t know.

AT: Well, I think it kind of really set the tone for the way we went about telling the story. Angelo Dundee is a guy who, whatever he talks about, he’s right back there in the moment – he’s just that sort of guy who lives and breathes this boxing world and with the twinkle in his eye, he is right back in the moment. He seems to have an incredible memory; although, no doubt watching the fight was a good aid to his memory – but the sort of immediacy of it was so powerful, the rest of the interviews kind of took their cue from that and the whole way we built the film.

SR: Was there a main point you wanted to make by the end of this film?

AT: This is sort of a round-about way in answering your question. But, who needs another Muhammad Ali documentary? Google or Amazon, you will find there are plenty out there. We thought this was one little story, one little window, that his Miami is, which goes a long way in explaining how this guy from Louisville, Cassius Clay, this “Louisville Lip” with predicting rounds and the gibberish and the rhyming became this enormous figure who totally transcends sport – and who resonates with people all over the world: white, black, green, orange – I mean he captures everybody’s imagination; most people positively. But how did he become Muhammad Ali? The fact of the matter is, he became Muhammad Ali during his Miami years. Most times when you make films they kind of take on a life of their own and this rapidly went beyond evoking the time and the place of Miami Beach and the boxing world, which were very important to us in the outset of the film. The heart of what the film is about is how this guy became Muhammad Ali — its one of those things when you start out by doing one thing and you wind up achieving something else. Your way of looking at Muhammad Ali is a little different – it takes you into a world and a time. You know I’m sixty, so I remember the Liston fight, Cassius Clay, and all that stuff – but my kids who are in their early twenties, love Muhammad Ali, and they never knew he was ever called Cassius Clay or that he spent any time in Miami Beach – and they have absolutely no idea how he became Muhammad Ali, his involvement with Malcolm X, and the background of the Civil Rights Movement of the time. So, why do we need another Muhammad Ali film? I mean this was an aspect of it that it just reminds you – Muhammad Ali has now become something almost mythical, he’s almost been sanctified by this point. But he’s just this kid that wanted to be this fighter for Christ sake. I’m always reminded of John Lennon who said, “I wanted to be Tom Jones and look what happened.” This guy wanted to be heavyweight champion of the world and look what happened – and that’s our story.

SR: This is sort of a rhetorical question, but in your opinion, will Muhammad Ali always be known as “the greatest?”

GG: I think that Ali as a figure of his moment and as a figure of the 1960’s – I mean the 1960’s are this era that is remembered as an age of revolt and revolution and transformation – and I think Ali will always be identified with that historical moment.

SR: So, it had a lot to do with the time period in which he came?

GG: Absolutely, to the degree that it was a significant era with the Civil Rights, anti-war movement, and all of that which I think what makes Ali’s place secure. But, you know as Alan sort of points out, that time sort of moves on and there are twenty year old kids who aren’t quite sure why he’s famous. They don’t have a memory of him as a fighter – he was a great fighter. Was he the greatest heavyweight fighter ever? He’s certainly the top three or four. You can argue that he was.

AT: There was another film out there that was made years ago. In fact it was filmed live at the time of the Liston fight, I saw a bit of it on the Independent Film Channel the other night, and someone asks Ali a provocative question and he says, “Listen, you’re the greatest if you think you are, let somebody prove you wrong.” I think there are a lot of boxing experts and analyst who would argue that Muhammad Ali isn’t their number one or two – I think it is Jack Dempsey or Joe Louis. But, there will never be another one like him. I don’t think there will never be a heavyweight as fast as he was and we’ve yet to see in any division a showman like him. In fact, a showman in boxing that we see these days is pretty much taking a leaf from Muhammad Ali’s book. A bit like Tiger Woods today, he certainly increased the size of the purses because people started watching boxing who never watched it before. Of course, that’s all gone now – nobody watches heavyweight boxing. I don’t watch heavyweight boxing. Who is the heavyweight champion of the world?

GG: Who, all six of them?

AT: Yeah, who cares? But back then everybody knew who the heavyweight champion of the world was. If you asked anybody in Ali’s time who was the heavyweight champion of the world, everybody would know. With that point, I don’t think there was anybody as greatly recognized – I mean what other boxer in any division, what other sportsman in any other sport could argue that he became the most famous face on the planet.

SR: Well, thank you guys once again for this opportunity.

GG: Sure, no problem, thank you.

(Be sure to check out Jeff’s review of the documentary.)

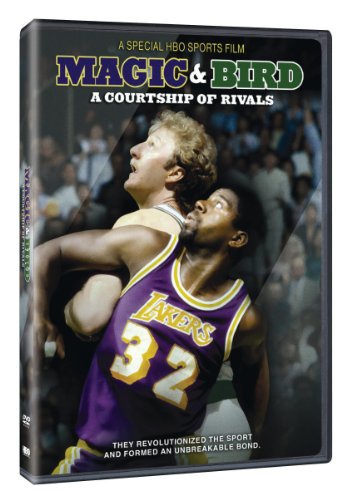

For years, the passion they shared for winning made Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Larry Bird the most bitter of rivals. It also made theirs the most compelling rivalry in sports, driving the NBA to new heights of popularity in the 1980s. Narrated by Liev Schreiber, this all-new documentary tells the riveting story of two superstars who couldn’t have been more different — until they forged an unlikely friendship from the superheated rivalry that had always kept them apart.

For years, the passion they shared for winning made Earvin “Magic” Johnson and Larry Bird the most bitter of rivals. It also made theirs the most compelling rivalry in sports, driving the NBA to new heights of popularity in the 1980s. Narrated by Liev Schreiber, this all-new documentary tells the riveting story of two superstars who couldn’t have been more different — until they forged an unlikely friendship from the superheated rivalry that had always kept them apart.